Once the Ministries of State building was finished, two commemorative stone plaques were placed on either side of the main entrance to celebrate the way in which a messy urban space had been transformed into "a single block of buildings, i.e. the San Giacomo island".

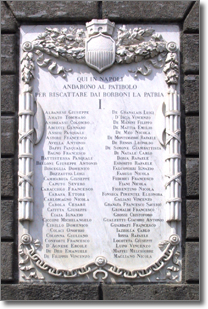

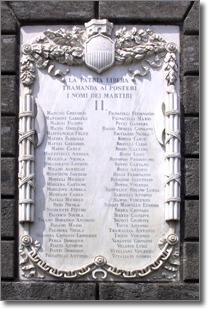

After the fall of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies the same fate awaited the stones as all the other ornaments which were a reminder of the Bourbon dynasty (see 1860, down with lilies and get rid of those kings). They were removed and, in 1865, substituted by marble plaques which still stand at the entrance to the building.

The new plaques commemorated the 116 patriots who were condemned for inciting insurgency against the monarchy in the period from 1794 to the end of the Kingdom of Two Sicilies.

The inscriptions are framed by a set of symbols, which, with the fasces down the two sides and the chains and broken ring along the bottom, symbolised the newly-found unity and liberty of the Italian Nation. The city's coat of arms is placed on top of oak and laurel branches, both of which remind us of heroism and celebrate its glory.

brief outline of the events involving the 116 patriots

The ideals of the French Revolution were quick to reach the South of the peninsula, inflaming the hearts and hopes of those who wanted a change of government in the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily. In 1794 a conspiracy was revealed. The conspirators were members of newly-formed Jacobin groups which included some famous names. 53 people were arrested, three of whom were sentenced to death by the High Court.

When the French troops arrived in Italy and entered the city of Naples, revolutionary ideals could really take hold. On 21st January 1799, the birth of the Neapolitan Republic was proclaimed.

The Republican experience lasted only a few months, however, until June of the same year when the Sanfedista army led by Cardinal Fabrizio Ruffo of the Princes of Scilla family, with back-up from the English navy under the command of Horatio Nelson, handed back the Southern provinces and the city to the crown. This marked the start of a long period of retribution which saw Piazza Mercato become the major venue for the many public executions.

Once Napoleon went out of favour, and the so-called French decade in the Kingdom of Naples was over and the second Restoration well under way, the idea of National Unification was still fairly popular.

Constitution and unitary ideals were spread by secret societies which had a lot of members drawn from the ranks of the Murat and Bourbon armies. In July, 1820, two cavalry officers led the revolt which would make King Ferdinand I decide to accept the constitution.

The sovereigns of Austria, Prussia and Russia did not approve the King's decision and they "invited" the Bourbon Ferdinand to take part in a conference in the city of Ljubljana. As a result of this, the Austrian army decided to intervene and marched into Naples on 23 March 1821. The Constitution was abolished and the Minister for the Police, Antonio Capece Minutolo, Prince of Canoso, was charged by the King to severely punish those responsible for the revolt.

The secret societies, despite persistent government control, still managed to inform and convince people about their republican and unitary ideas. In 1823 new sects with Jacobin ideals were discovered in Naples, Capua, Lanciano and in the Citeriore Principality and the gallows was put back to macabre use once more.

In 1828, members of the Carbonara sect known as the Filadelfi, with a lot of support from the local population, started a revolt in the Cilento hills. The reaction was immediate and sections of the army under the command of Field Marshall Marquess Francesco Saverio del Carretto, encircled the whole area forcing almost all the rebels to surrender. They were immediately sent to trial and it was decided that those who received the death sentence would be shot to death and their heads cut off and displayed in cages as a warning to the people.

Episodic revolts continued throughout the various provinces in the Realm and towards the end of 1847 the insurrection committee of Naples decided to organise a popular uprising to coincide with similar protests in Messina, Reggio Calabria and the Gerace district. Their attempt failed and the result was that more people were executed.

The Bourbon Kingdom was drawing to a close when on 8 December, 1856 at the Campo di Marte in Naples, the troops were involved in a big parade in honour of the Immaculate Conception when a twenty-six-year old soldier stepped forward, marched up to the King who was on horseback and hit him with his bayonet. As luck would have it, the blade veered and the wound was fairly superficial. The soldier, Agesilao Milano, was hanged five days later in the largo del Cavalcatoio (known as piazza San Francesco today, just outside the Capuana Gate).

The names were listed in alphabetical order on the stones. On the information sheets, on the other hand, the names are listed under the year the event they were involved in took place.

The biographical information comes from:

Area Cultura e Turismo Servizio Beni Culturali - Archivio Storico Municipale

Salita Pontenuovo, 31 - 80139 Napoli

e-mail: archivi.storici.biblioteche@comune.napoli.it

pec: archivi.biblioteche@pec.comune.napoli.it